When our correspondent was abruptly summoned to an audience with the legendary artist in his Minneapolis studios, he had no idea what to expect. Certainly not being asked to duet on Sign o the Times …

In 1985, Prince released a single called Paisley Park, the first to be taken from his psychedelic opus, Around the World In a Day. Its one of several Prince songs that describe a location thats a kind of mystical utopia.

Paisley Park, the lyrics aver, is filled with laughing children on see-saws and colourful people with expressions that speak of profound inner peace, whatever they look like. Love is the colour this place imparts, it continues. There arent any rules in Paisley Park.

Its all a bit difficult to square with Paisley Park, the vast studio complex Prince built a couple of years later. It sits behind a chainlink fence in the nondescript Minnesota suburb of Chanhassen, and theres no getting around the fact that, from the outside at least, it looks less like a mystical utopia, more like a branch of Ikea.

Inside, however, it looks almost exactly like youd imagine a huge recording complex owned by Prince would look. There is a lot of purple. The symbol that represented Princes name for most of the 90s is everywhere: hanging from the ceiling, painted on speakers and the studios mixing desks, illuminating one room in the form of a neon sign.

There is something called the Galaxy Room, apparently intended for meditation: it is illuminated entirely by ultraviolet lights and has paintings of planets on the walls. There are murals depicting the studios owner, never a man exactly crippled by modesty.

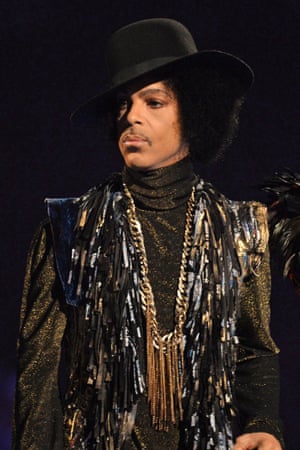

And there are two full-sized live-music venues: a vast, hangar-like space that also features a food concession form an orderly queue for Funky House Party In Your Mouth Cheesecake ($4) and a smaller room decked out to look like a nightclub. I am currently on the stage of the latter, along with four other representatives of the European press.

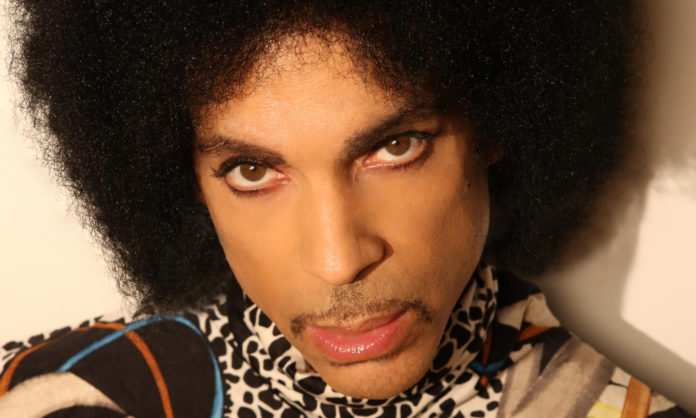

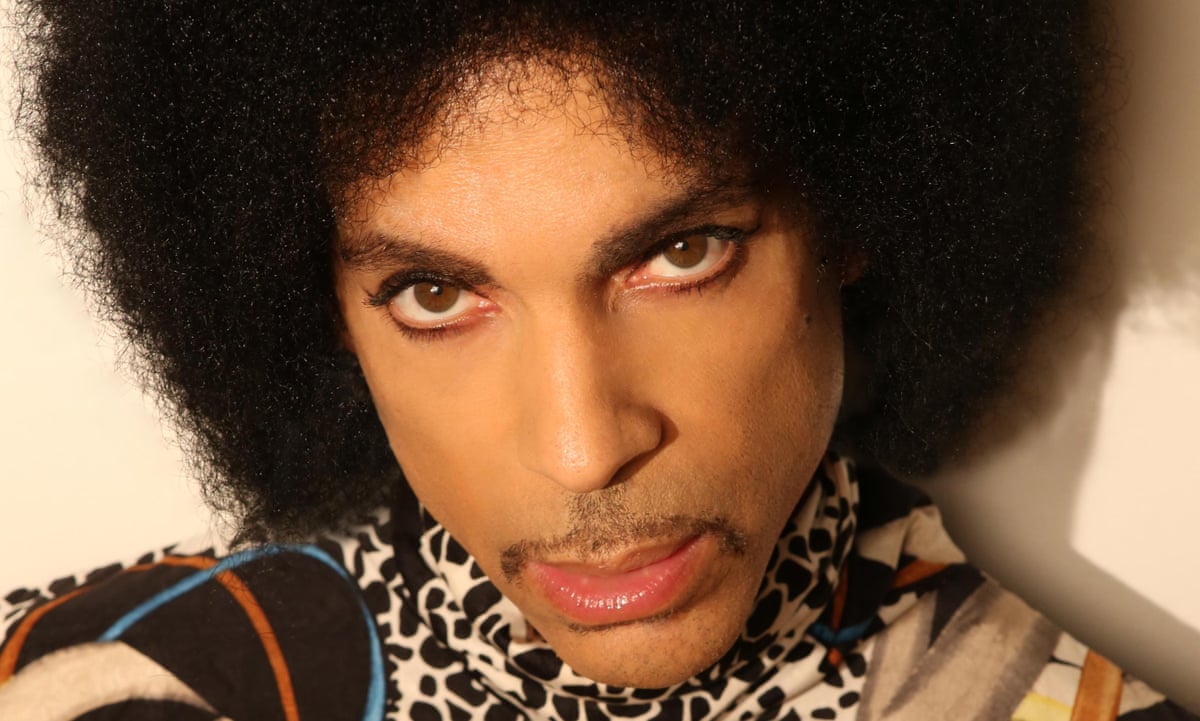

We are literally sitting at Princes feet: feet, its perhaps worth noting, that are wearing a pair of flip-flops with huge platform soles teamed with socks. The socks and flip-flops are white, as is the rest of his outfit: skinny flared trousers, a T-shirt with long sleeves, also flared. As skinny as a teenager, sporting an afro and almost unnecessarily handsome at 57 years old, Prince looks flatly amazing, exuding ineffable cool and panache while wearing clothes that would make anyone else look like a ninny is just one among his panoply of talents.

We are seated at his feet because we are supposed to be asking Prince questions: weve been summoned to Paisley Park at short notice, apparently because Prince had a brainstorm in the middle of the night, two nights ago and decided this was the best way to announce a forthcoming European tour.

First, there was a tour of the studio accompanied by Trevor Guy, who works for Princes record label NPG: hes friendly, effusive about his bosss talents and a little evasive when someone asks him whereabouts in Minneapolis Prince actually lives. (He doesnt live here. I dont know where he lives.)

Then we were told we were getting a treat, which turned out to be listening to some cover versions Princes current protege, Andy Allo, recorded with the man himself on guitar. While were listening to Andy Allo sing Roxy Musics More Than This, Prince suddenly appears on the stage and beckons us over.

The dates havent actually been confirmed yet, but the concept has: hes going to perform solo, playing the piano, in a succession of theatres. Well, Im not one to get bad reviews, he deadpans.

So Im doing it to challenge myself, like tying one hand behind my back, not relying on the craft that Ive known for 30 years. I wont know what songs Im going to do when I go on stage, I really wont. I wont have to, because I wont have a band. Tempo, keys, all those things can dictate what song Im going to play next, you know, as opposed to, Oh, Ive got to do my hit single now, Ive got to play this album all the way through, or whatever. Theres so much material, its hard to choose. Its hard. So thats what Id like to do.

Prince, it has to be said, is proving the very model of softly spoken charm. Hes also wryly funny on topics ranging from his songwriting (I have to do it to clear my head, its like shaking an Etch a Sketch) to the activist Rachael Dolezal, or as he puts it, that lady who said she was black even though she was white, to his famous 2010 pronouncement that the internet is completely over.

What I meant was that the internet was over for anyone who wants to get paid, and I was right about that, he says. Tell me a musician whos got rich off digital sales. Apples doing pretty good though, right?

Its all a far cry from the days when he refused to talk to the press, disparaged them in song Take a bath, hippies! he snapped in 1982s All The Critics Love U In New York or dismissed them mamma-jammas wearing glasses and an alligator shirt behind a typewriter.

Oh, I love critics, he smiles. Because they love me. Its not a joke. They care. See, everybody knows when somebodys lazy, and now, with the internet, its impossible for a writer to be lazy because everybody will pick up on it. In the past, they said some stuff that was out of line, so I just didnt have anything to do with them. Now it gets embarrassing to say something untrue, because you put it online and everyone knows about it, so its better to tell the truth.

Nevertheless, its turning out to be harder to ask questions than you might think. Prince is seated at a microphone behind a keyboard, which he keeps playing. This is quite disconcerting: if he doesnt like a question, he strikes up with the theme from The Twilight Zone and shakes his head. At one point, he presses a button on the keyboard and the intro to his legendary 1988 hit Sign o the Times booms out of the PA.

He looks at me. You wanna do this? he says. I look back at him aghast: there are doubtless things I want to do less than sing Princes legendary 1988 hit Sign o the Times in front of Prince, but at this exact moment Im struggling to think of any. For one thing, Prince is, by common consent, the one bona-fide, no-further-questions musical genius that 80s pop produced; a man who can play pretty much any instrument he choses, possessed of a remarkable voice that can still leap effortlessly from baritone to falsetto.

I, on the other hand, am a deeply unfunky Englishman with no discernible musical ability: the sound of my singing voice can ruin your day. For another, Im a journalist, and thus aware that among Princes panoply of talents lies a nonpareil ability to screw with journalists. Rumours abound of him demanding hacks dance in front of him. Only if their gyrations are deemed sufficiently funky do they get face time.

A recent visitor to Paisley Park found himself standing in the studio having a telephone conversation with Prince, who, it later transpired, was standing in the next room all along. The novelist Matt Thorne, author of a 500-page book that stands as the definitive work on Princes oeuvre, tells a story of pursuing him for an interview, and being invited to attend a gig in New York.

Midway through a guitar solo, Prince spotted Thorne in the audience, walked over, whispered: How about that interview? then ran off, still soloing: Thorne never heard from him again. So I shake my head and say no: for a mercy, Prince shrugs and turns the music off and we plough on, albeit a little awkwardly.

Without wishing to bore you with the mechanics of interview technique, its hard to get a conversational beat going or indeed to chase up answers that seem evasive or tangential to the actual question when there are four other people there, eager to have their say, among them a man who appears to have travelled from France with the specific intention of not asking any questions, but simply impressing on Prince how many times hes seen him live, and an Italian journalist keen to know how the artists latterday religious beliefs affected what he insists on referring to as his Sex Issues.

The latter is actually a fair question: few artists in history have had musical Sex Issues on quite the scale that Prince did. Incest (Sister), references to rape (Lust U Always), a queasy description of his first sexual partners vagina (Schoolyard): before becoming a Jehovahs Witness, Prince once considered this all fair game in his concerted effort to shock.

It would be intriguing to know where he draws the line now among the covers he and Andy Allo recorded was an old song of his, I Love U in Me, which is hardly Sunday school fare, while a journalist invited to Paisley Park to hear his recent album Plectrumelectrum was startled to see Prince run from the room when a particularly spicy lyric hed forgotten about blared from the speakers but his answer is a little vague. It just makes me think more in terms of detail.

Could I say things better, more succinctly, more truly? And wider, for example, if you want kids to come to your concerts. Now Ive got older fans, they have families, so they want to bring their kids, so I think its a pretty good move to take some of those songs out, so you can get a bigger audience, to experience the same thing.

No, he says, he never considered just changing the lyrics of a beloved but filthy old song like Head or Darling Nikki so that he could still perform it. You want to hear it? Its on an album. I write so many songs that I dont even think about those songs any more. I dont get attached to it. Because if I did, I couldnt move on and thered be no space for a new song like Stare. Thats what you want to listen to.

The subject that really gets him going is his famous bete noir, the music industry. Hes dallied with a number of record labels since his legendary 90s dispute with Warner Brothers, but hes still given to describing record business contracts as slavery, protesting that the industry gives black artists a rough deal I think history speaks for itself. You know, U2 dont have a problem with their label. They love their record label and advising new artists not to sign anything.

Larry King asked me once, didnt you need a record company to make it [in the music business]? But that has nothing to do with it. I was well known starting out, we had a great band and every time we played, we got better. We also had studio work, so the more we recorded the better we got. This is what youve got to do, and if youve got great folk around you and a good teacher, youre going to excel at it.

You dont need a record company to turn you into anything. It wasnt like they were directing our flow whatsoever, you know. I had autonomous control from the very beginning to make my album.

He says theres no danger in modern music: When was the last time you were scared by anyone? In the 70s, there was scary stuff then. He suggests that the blame for any malaise lies not merely with the record companies accountants and lawyers stepped in while producers were in the studio, they started looking for things that they thought would work, so dozens of rock bands come out every week and you cant even name them but also a lack of jazz-fusion bands. The latter, you have to say, seems a fairly unique interpretation of the situation.

Well, I dont think people learn technique any more. There are no great jazz-fusion bands. I grew up seeing Weather Report, and I dont see anything remotely like that now. Theres nothing to copy from, because you cant go and see a band like Weather Report. Al di Meola, the guitar player, hed just stand in the centre of the stage, soloing, until everyone gives him a standing ovation. Those were the memories that I grew up with and that made me want to play.

Hes keen to emphasise that its an urge thats never left him. Last night, he says, he sat here alone, after everyone else had gone home, and played and sang for three hours straight. I just couldnt stop, he says. Hed got in the zone like an out-of-body experience: it felt like he was sitting in the audience watching himself. Thats what you want. Transcendence. When that happens he shakes his head Oh, boy.

Still, it seems an oddly lonely image: sitting in an empty building in the middle of nowhere in the small hours. It makes me think of a heartbreaking interview he gave to Rolling Stone in the mid-80s, when he was clearly struggling to come to terms with the isolating effects of global superstardom.

He invited the writer back to his house and confided that his then-girlfriend had offered to show up while the journalist was there to make it seem like you have friends come by, but Prince had declined because that would be lying. I ask if theres anything he still misses from the years before he became one of the biggest stars in the world.

No, he says firmly. These days, I can get more done. Im far more respected than I was before, when I say something with regard to changes in the music industry. And then he changes the subject to Jay-Zs streaming service Tidal, with which Prince has recently signed, and draws the interview to a close: Are we good?

Later that night, hes back on the stage again, playing one of the regular secret Paisley Park shows that locals pay $40 to attend, unaware of whether Prince will actually perform or not. I sit next to a mother and daughter who have turned up on three occasions: the only previous glimpse they got of Prince was spotting him riding a bicycle around the car park, which I suppose is a sight worth seeing in itself.

When he sits back at the piano and plays Raspberry Beret and Starfish and Coffee and Girls and Boys, theyre beside themselves, and understandably so: he sounds magnificent. He plays covers of songs by of the Staples Singers and Chaka Khan, and a couple of funk jams with his band.

Then he invites the audience to come to the cinema and watch the new James Bond film with him, and vanishes before anyone can try take him up on the offer: presumably hes gone home, wherever that is.

Read more here: http://www.theguardian.com/us